|

Calliope Wholesale Hay & Feeds |

|

Risks and some little known facts about Rabies

Understanding which horses are at most risk of contracting rabies, and why, by knowing the basic facts about this devastating disease.

The Rabies virus does not come to mind often anymore because of widespread vaccinations over the last century have greatly diminished the threat. In fact, among horses it is a very rare occurrence. According to the CDC there were only 53 reported cases in 2006 that involved horses.

While it is somewhat comforting that rabies is so rare, it is nevertheless a frightening prospect. In general, rabies is transmitted by infected animals through their bite, once in the body the virus enters the central nervous system with fatal result. The fact that the odds for contracting rabies are extremely low does nothing to ease the invariable dire consequences of an encounter. The CDC reports that “rabies has the highest fatality rate of any infectious disease”. (1)

So as remote a possibility as it seems, a rabies threat is a serious subject not to be taken lightly. Vaccination is the clearest avenue towards peace of mind, and it’s an easy process, very effective and inexpensive. Knowing if your horse is at risk, and why, will go a long way in helping you determine if vaccination is key.

Rabies (hydrophobia) Basics (3) :

These basics underscore the fact that as remote a possibility of rabies contraction may seem to you, it should indeed be taken seriously.

Some little known facts about rabies:

Rabies travels through the nerves, not the bloodstream, to the spinal cord and brain. It is generally transmitted by saliva-to-nerve contact which occurs most often during the bite from an infected animal.

Entering the muscle and neural tissue near the site of the bite, the virus quickly moves on to the nearby peripheral nerves. The virus has protruding spikes that enable binding to nerve cells and receptors. In the process of self replication and receptor simulation it transfers itself from nerve cell to nerve cell working its way to the final goals of spinal cord and brain.

During this incubation process no signs of disease appear in the animal, yet once it reaches the brain it replicates abundantly and spreads back out into the body through the nerves and into the glands the symptoms rapidly appear. Once this acute stage of rabies is reached and the symptoms are readily apparent, the horse has literally only days to live.

Once in this acute period the virus is likely present in the saliva of the infected horse and further transmission to other horses is a real threat. A bite to the head or face of another horse would allow for a very quick incubation period as the virus will not have far to travel to the brain. Horses that have received a bite from a carrier suspect would be wisely quarantined for this reason.

While rabies can be contracted by all mammals, some are much more susceptible than others, and these develop the infection more easily from even slight exposure.

As is common with viruses, there are more than a dozen variants in existence, each one more finely tuned to a particular host species. Major hosts in North America, because of their high susceptibility, include skunk, fox, raccoon and bat. These animals can fall ill even after limited exposure to their own variant and transmission is rapid within the same species in the area.

Sometimes though, a more resistant animal species may host the virus, needing a much more concentrated exposure to contract the virus, yet transmission from them is considered rare. Confirmation that supports survival in the wild from the virus has come from a study presented in the Journal of Wildlife Diseases where researchers trapped a Bolivian Oncilla (also known as the ‘little spotted wildcat) that had a presence of naturally formed rabies antibodies in its system as high as a vaccinated animal’s antibody level would be.

Where a horse is bitten has a lot to do with survival of an unvaccinated horse. While a horse is considered highly susceptible to rabies when compared with other animals, the size and features of the anatomy help to minimize risk.

Long legs with relatively sparse nerve tissue create a more difficult environment for the virus to travel to the spinal cord and brain. The distance and sparse avenues give the immune system more time to combat the invasion, a battle the horse sometimes wins.

Now if the bite is on the face or muzzle, we have a different situation altogether. Filled with facial nerves a short distance from the brain, a bite in this area can be deadly quick in causing a full infection with little hope of survival.

Where the virus is introduced and how much of it was delivered in the bite both play a part in the length of the incubation period and how quickly symptoms will appear. A head or facial bite may take only days for the virus to take over, while a bite to the leg may take up to six weeks in a losing battle.

While post-exposure treatment of humans has been developed, a crossover method to animals does not currently exist. One reason may be the cost effectiveness of the research needed is prohibitive in comparison with the relatively inexpensive method of vaccination.

Once a horse has been bitten and the virus has taken hold, its condition worsens quickly. Unless the horse can be quarantined and monitored for up to six months, euthanasia is advised by the CDC and many veterinarians.

Symptoms may vary widely as horses may develop different forms of the disease dependent upon several variables, including bite location, severity of the wound, and level of infection in the host animal.

Acute signs most often appear with a bite to the head and include hyperactivity, agitation and aggression, facial and oral paralysis. A leg bite is more likely to result in a paralytic syndrome evidenced by depression, ataxia, weakness, recumbency, paralysis and excessive salivation. Some horses may present symptoms of both syndromes, with all becoming recumbent prior to death. Once clinical signs such as these appear, there is no treatment against the virus.

The presentment of some of the early symptoms associated with rabies may have actually other causes. Depression, weakness or in-coordination may be associated other equine neurological conditions. At other times it may present as lameness or even colic symptoms, all of this making diagnosis even more difficult.

Since rabies cannot be easily identified through analysis of bodily fluids in a living animal, the veterinarian is left mostly to the animal’s history and if a bite is overlooked as a scratch or something minor, then a critical clue is absent and correct diagnosis becomes even more difficult.

And since the disease progresses rapidly it may only take a few days for a veterinarian to confidently identify rabies as the culprit, however, certain diagnosis is only possible through post-mortem analysis of brain tissue.

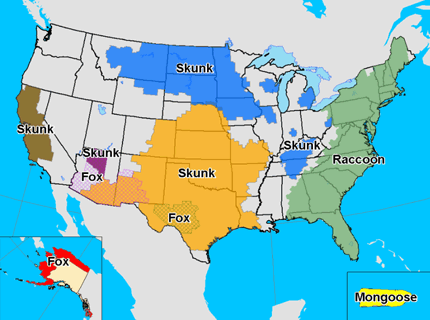

Rabies has been found in every state in the union with the exception of Hawaii. Despite your distance from reservoir sites identified in the CDC’s map there is still risk of contraction.

It is for you to decide when to provide an ounce of prevention in case of an occurrence which has no cure. For many, vaccination is an easy, cost effective defense against a devastating virus no matter how remote the threat may seem.

Is your area at high risk? The CDC says (2): “Wild animals accounted for 92% of reported cases of rabies in 2009. Raccoons continued to be the most frequently reported rabid wildlife species (34.8% of all animal cases during 2009), followed by bats (24.3%), skunks (23.9%), foxes (7.5%), and other wild animals, including rodents and lagomorphs (1.9%). Reported cases decreased among all wild animals during 2009 with the exception of an increase among skunks and foxes. Outbreaks of rabies infections in terrestrial mammals like raccoons, skunks, foxes, and coyotes are found in broad geographic regions across the United States. Geographic boundaries of currently recognized reservoirs for rabies in terrestrial mammals are shown on the map below:”

Map of terrestrial rabies reservoirs in the United States during 2009. Raccoon rabies virus variant is present in the eastern United States, Skunk rabies in the Central United States and California, Fox rabies in Texas, Arizona, and Alaska, and Mongoose rabies in Puerto Rico. “Domestic species accounted for 8% of all rabid animals reported in the United States in 2009.” While the above map is a good indicator of how prone your area is to the virus, keep in mind that even the un-shaded areas on the map are not 100% free of instances. Vaccination recommendations (3):

“Four types of rabies vaccine have been approved for use in horses. Currently, horses receive an inactivated (killed-virus) product, which is administered annually.

Ask your veterinarian if rabies vaccination is a good idea for your horses. The answer probably depends on the part of the country where you live and the likelihood of exposure to wild animals, at home or on the trails. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommends vaccination for animals that travel between states and have frequent contact with the public, such as those that travel to fairs and shows.

The American Association of Equine Practitioners recommends vaccinating horses in endemic areas, parts of the country where rabies is known to exist in higher numbers among the local wildlife (see map).”

This inspiration for this article came from various sources, including the good folks at EQUUS magazine. We heartily recommend further reading at http://www.equisearch.com.

References: 1. Charles Rupprecht, VMD, PhD, chief of the rabies program at the CDC. 2. Center for Disease Control 3. Equus Magazine January 2008, issue 364 4. Images from the CDC and Wikipedia.org

|

|

|

|

|

|

Proudly serving all of Southern California, including the counties and areas of: Santa Barbara, Ventura, Inyo, Kern, Los Angeles, Orange, San Diego, Inland Empire, Riverside, San Bernardino and Imperial.

|

|

Call (760) 774-4212 Email FAX (760) 868-6162 Copyright 2011 Calliope Wholesale Hay and Feed Site designed and maintained by TKJConsult.com |